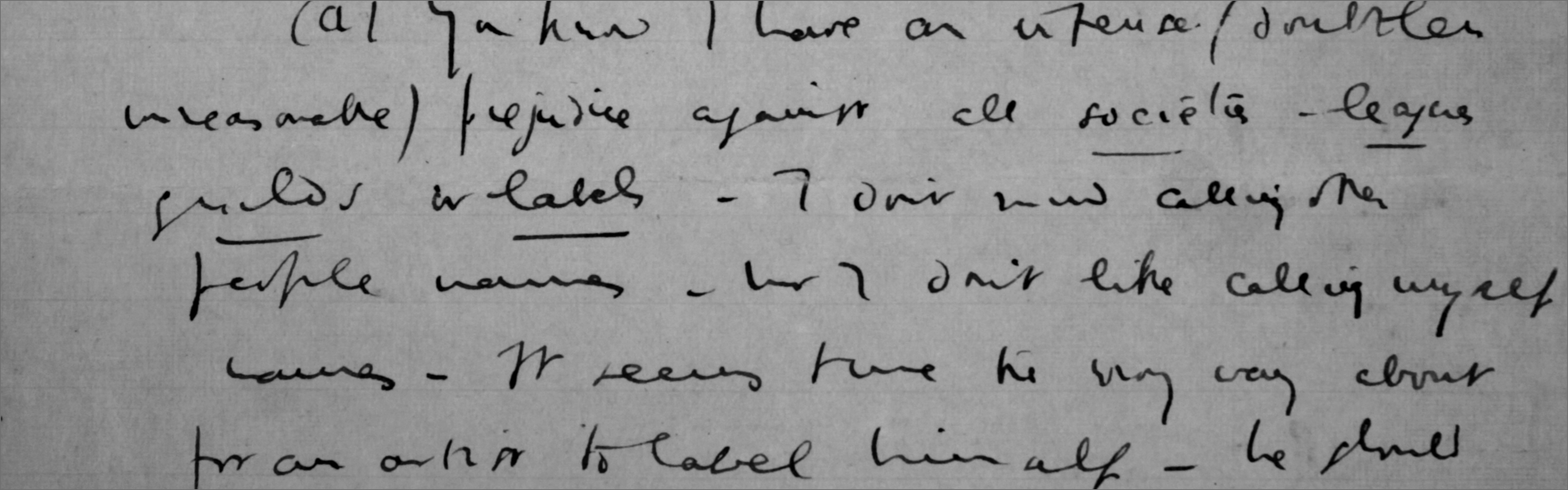

Letter from Ralph Vaughan Williams to Sir Alexander Kaye-Butterworth

Letter No. VWL435

Letter from Ralph Vaughan Williams to Sir Alexander Kaye-Butterworth

Letter No.: VWL435

RA Mess

Hut Town

Lydd.

Dec 2nd 1917

Dear Sir Alexander

I am sending a few words which I have tried to write about George – I wish it was more worthy – if you wd care to do so please use part or all of it as you think best.1 I am sorry it is in pencil but pens and ink are hard to come by here.

I am enclosing George’s letter from which I quote – I feel you may care to keep it.

Cecil Sharp is still in America. I wish he cd have written something.

Yours sincerely

R. Vaughan Williams

___________________________________________________________________

One of my most grateful memories of George is connected with my “London Symphony”. Indeed I owe its whole idea to him. I remember very well how the idea originated. He had been sitting with us one evening talking, smoking & playing (I like to think that it was one of those rare occasions when we persuaded him to play us his beautiful little Pianoforte piece “Firle Beacon”). At the end of the evening just as he was getting up to go he said in his characteristically abrupt way “You know, you ought to write a symphony”. From that moment the idea of a symphony – a thing which I had always declared I would never attempt – dominated my mind. I showed the sketches to George bit by bit as they were finished – and it was then that I realised that he possessed, in common with very few composers, a wonderful power of criticism of other men’s work and insight into their ideas and motives.

I can never feel to[o] grateful to him for all he did for me over this work – and his help did not stop short at criticism. When Ellis suggested that my symphony should be produced at one of his concerts I was away from home and unable to revise the score myself and George together with Ellis and Francis Toye undertook to revise it and to make a “short score” from the original – George himself undertook the last movement.2

There was one passage which troubled him very much – but I could never get him to say exactly what was wrong with it – All he would say was “It won’t do at all”. After the performance he at once wrote to tell me he had changed his mind – He wrote

“A work cannot be a fine one until it is finely played – and it is possible that [other of my music works] may turn out equally well … I really advise you not to alter a note of the Symph: until after its second performance … The passages I kicked at didn’t bother me at all because the music as a whole is so definite that a little occasional meandering is pleasant rather than otherwise. As to the scoring, I frankly don’t understand how it all comes off so well, but it does all sound right, so there’s nothing more to be said…..”3

Another musical meeting ground for George and myself was the English Folksong for which he did so much and which did so much for him. It has often been my privilege to hear him improvise harmonies to the folk-tunes which he had collected, bringing out in them a beauty and character which I had not realised when merely looking at them. This was not merely a case of “clever harmonisation”, it meant that the inspiration which led to the original inception of these melodies and that which lay at the root of Butterworth’s art were one and the same and that in harmonising folk-tunes or using them in his compositions he was simply carrying out a process of evolution of which these primitive melodies and hs own art are different stages.

When I first knew George’s compositions the traces of that individuality whch was so pronounced later on were, indeed, to be found – but hindered and checked to a certain extent by the indluence of Schumann & Brahms and partly by what may be described as the “Oxford manner” in music – that fear of self-expression which seems to be fostered by academic traditions.

It was the folk-song which freed Butterworth’s art from its foreign surroundings. To George Butterworth the folk-song was a means of freedom which enabled him to throw off the fetters which hindered his earlier efforts and formed a nucleus whch focussed his hitherto vague stirrings after those things at whcih he really aimed. It is certain that his study of folk-song coincided with the development of his real musical self. To him the folk-song as a basis of musical inspiration was not merely “playing with local colour[”] – his most beautiful composition the “Shropshire Lad” for example or the Henley songs4 have no direct connection with any folk-tune – but their influence was no less clearly to be seen than in the “Idylls” in which he definitely took folk-music as the thematic basis.5 Indeed he could no more help writing in composing in his own national idiom than he could help speaking his own mother-tongue.

R. Vaughan Williams

1. George Butterworth’s parents were compiling a memorial volume, George Butterworth 1885-1916 (York and London, 1918) for private circulation.

2. VW was in Italy at Ospedaletti, on war service.

3. This passage, taken from the text published in the memorial volume, is printed in R.V.W.: a biography, p.111. The original letter is VWL395.

4. Butterworth’s rhapsody A Shropshire Lad of 1912 and Love blows as the wind blows, a cycle of for settings of poems by W.E. Henley for voice and string quartet of 1914.

5. Two English Idylls of 1911 and The Banks of Green Willow of 1913.

-

To:

-

From:

-

Scribe:

-

Names:

-

Subject:

-

Places:

-

Musical Works:Butterworth, George, 1885-1916. A Shropshire LadButterworth, George, 1885-1916. Banks of green willowButterworth, George, 1885-1916. Love blows as the wind blowsButterworth, George, 1885-1916. English idyllsVaughan Williams, Ralph, 1872-1958. Symphonies, no. 2, G major (London Symphony)Butterworth, George, 1885-1916. Firle Beacon

-

Format:

-

Location Of Original:

-

Shelfmark:MS Eng.c.3269, ff.124-131

-

Citation:Cobbe 108