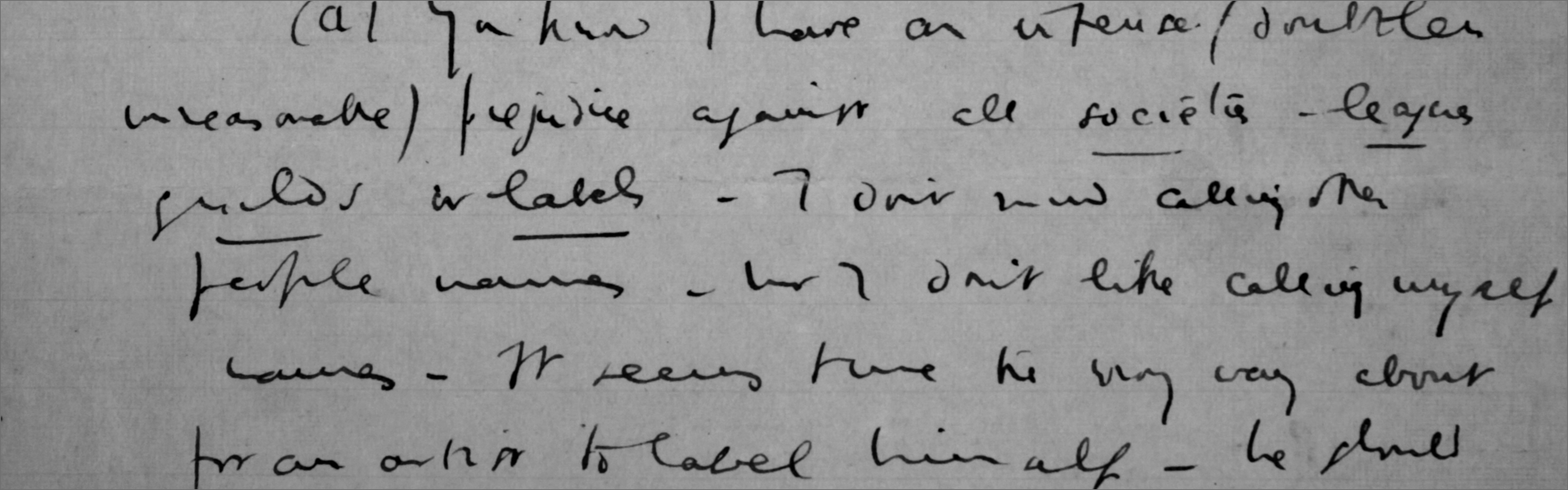

Letter from Gustav Holst to Ralph Vaughan Williams

Letter No. VWL5226

Letter from Gustav Holst to Ralph Vaughan Williams

Letter No.: VWL5226

Berlin

Monday [1903]

Dear RVW

I went to Jesus1 but I didn’t drink. He was awfully nice and kept me an hour and a half. But he said that the tune at the end of the Drapa and the Invocation were written too much in the ‘popular English style’ to be of any use in Germany. In fact he seems to think that I had written both things in order to suit Messrs Chappel & Co. If I had time I would tell you about an awful German-American professor that he took me to but that must wait as I have so much to say that is more important, for the professor turned out to be an utter fraud.

Now then to business.

I really cannot feel concerned about your fears that all your invention has gone. I am sorry but it is impossible. You got into the same state of mind just before you wrote the Heroic Elegy so that I look on it as a good sign and quite expect to hear that you have struck oil when you write again.

I have thought about it a good deal and these are some of my conclusions.

1) You have never lost your invention but it has not developed enough. Your best – your most original and beautiful style or atmosphere is an indescribable sort of feeling as if one was listening to very lovely lyrical poetry. I may be wrong but I think this (what I call to myself the real RVW) is more original than you think.

But when you are not in this strain, you either write ‘second class goods’ or you have a devil of a bother to write anything at all. The latter state of mind may seem bad while it lasts but it is what you want to make yourself do for however much I like your best style it must be broadened. And probably it is so each time you get into a hopeless mess. Probably you are right about mental concentration – that is what you want more than technique. For that reason perhaps lessons would do you good but it would be a surer way to try and cultivate it ‘on your own’.

In one of Parry’s2 lectures he played all the sketches Beethoven made for the ‘Eroica’ Funeral March (first theme). Sketch no 1 was not at all bad. No 3 was beautiful. No 6 was stupid. No 9 was bloody. The final one was a return to No 3. The moral of which is that if you spoil good stuff by working at it you must spoil the spoiliation by more work. Of course waiting plays a small part but I think you are wrong in thinking that working at a theme or idea will ruin it. Even suppose the working out is not so good as the original you can always go back and then you will have the result of your experience into the bargain.

I know there is a good deal to be said for the other side but I think that the only true waiting for ideas is the waiting or resting after a long spell of hard work.

Then again when you spoil good ideas is not that because you write too much – that is you go ahead too fast – instead of grinding away bar by bar which is the only true hard work?

Would it be good, do you think, for your to rewrite as a matter of course everything you write about six months after it is finished? (Really finished, not merely sketched). Whenever I have re-copied or re-scored anything, I have improved it very much. Anyhow I would never score at once – wait until your mud pie is hardened and until you can compare it in cold blood to others.

Another idea of mine is madder and perhaps even harmful but anyhow you shall have it. Cannot invention be developed like other things? And would not it be developed by you trying to write so many themes every day? Three decent themes a day for instance (probably in trying, you would get a few more that were verging on indecency). Then at the end of a week you could see how many were worth anything.

I am sure I am right about us being too comfortable. When you work hard you merely cover a lot of ground instead of making sure of your ground as you go on. (This is not absolutely true but I think you have a tendency that way).

Another thing we must guard against and that is getting old! Especially you – I am more juvenile than ever, I think, but I have my doubts about you. As I said before we have so much to contend against and in England there is no one to help, so that progress is sure to be a bit erratic. For instance, I doubt whether your Rhapsody will sound half as good as the Elegy and if you feel old you will be disappointed. Whereas the real truth is the Elegy was a climax and the Rhapsody a new start – a broadening-out – which will in the long run probably do you far more good.

As for me I think I have got careless owing to Worming3 and pot-boiling. For I am certain that Worming is very bad for one – it makes me so sick of everything that I cannot settle down to work properly. And pot-boiling as I have done it is bad because I got into the way of thinking that anything would do. Whereas we must write now chiefly so that we may write better in the future. So that every detail of everything we do must be as perfect as possible. For the next few years not only ought we to write more carefully than we have ever done before but more carefully than we need ever write again. My wife has had another idea which I think I shall adopt. That is that when we return I shall not take any Worming job or go out of London until the Scottish begins.4 If I can get a theatre well and good, if not I will even accept your offer of lending me money rather than play two or three times a day. (You see our living in London is pretty cheap). Then I should like to try to work systematically from August to November both at writing and studying music. I rather think you know more music than I do, anyhow I am sure I don’t know enough about Beethoven’s sonatas or Schubert’s songs and heaps of other things. I wonder if it would be possible to lock oneself up for so many hours every day. If so it would be far easier for me than for you as you have so many friends. I feel it would be so splendid to ‘go into training’ as it were, in order to make one’s music as beautiful as possible. And I am sure that after a few months’ steady grind we should have made the beginning of our own ‘atmospheres’ and so should not feel the need of going abroad so much. For it is all that makes up an ‘atmosphere’ that we lack in England. I am sorry I have to make such a commonplace remark. Here people actually seem anxious to hear new music, still more wonderful, they even seem anxious to find out all about a new composer! That in itself would work a revolution in England!

By the bye I am certainly going to rewrite the words of Sita as you suggest. They are disgraceful and that was largely due to Worming etc. I used to write them at odd moments, often in the orchestra.

Which reminds me – one may get hold of a decent theme on the top of a bus etc but I deny utterly that one can do ‘splendid work’ there – especially the work we most need. I used to be proud of writing things at odd times. It was great fun but it was damned rot and it helped on my present carelessness. I should like to keep up this kind of correspondence all the time I am away. Don’t you think it might do us good? Only you must tell me more about yourself.

One problem puzzles me. Is it really bad to write at the piano? I try one or the other as it suits me best. If it is bad, wherein does the badness lie and what bad results accrue from it?

Do you think it would be good to give ourselves a small dose of what Wagner had – analysing a sonata and then writing one in the same style and form? Anyhow don’t you start counterpoint – it’s the thing after that that we need. Also you might follow the advice you gave me – to cultivate a more leisurely frame of mind when composing. Perhaps you don’t need it so much as I do but I think you do in another way. Namely you must feel young (you are absurdly young for a composer and for an English composer you are hardly hatched!) and if a thing does not come off after a day’s or a week’s working, then that working will make its due effect when you are grown up.

I wish you could have a holiday now, and then have a grind like I propose doing – that is, if you think it a good plan. It would be more fun if we did it together although perhaps there is nothing in it.

After much deliberation we have decided not to bicycle to Dresden and probably not from there to Munich. What do you think about the latter? I think we can neither spare the money or the time. The latter is especially important as we must see the Tyrol. Also a long ride like that would mean getting into training beforehand and a lot more rest afterwards for which we have no time as I think it more important to see operas, picture, people, and cities than the country barring the Tyrol. Of course we shall have short rides. Address till I write again

Poste Restante, Dresden

Yours ever

G v H

1. Unidentified – possibly someone at Jesus College, Cambridge?

2. Charles Hubert Parry, Professor at the Royal College of Music.

3. Holst played the trombone in a popular orchestra called the ‘White Viennese Band’, conducted by Stanislas Wurm.

4. Holst was engaged to tour as trombonist with the Scottish Orchestra.

-

To:

-

From:

-

Scribe:

-

Names:

-

Subject:

-

Places:

-

Musical Works:

-

Format:

-

General Notes:

Text taken from Heirs and Rebels.

-

Citation:Heirs and Rebels, Letter X