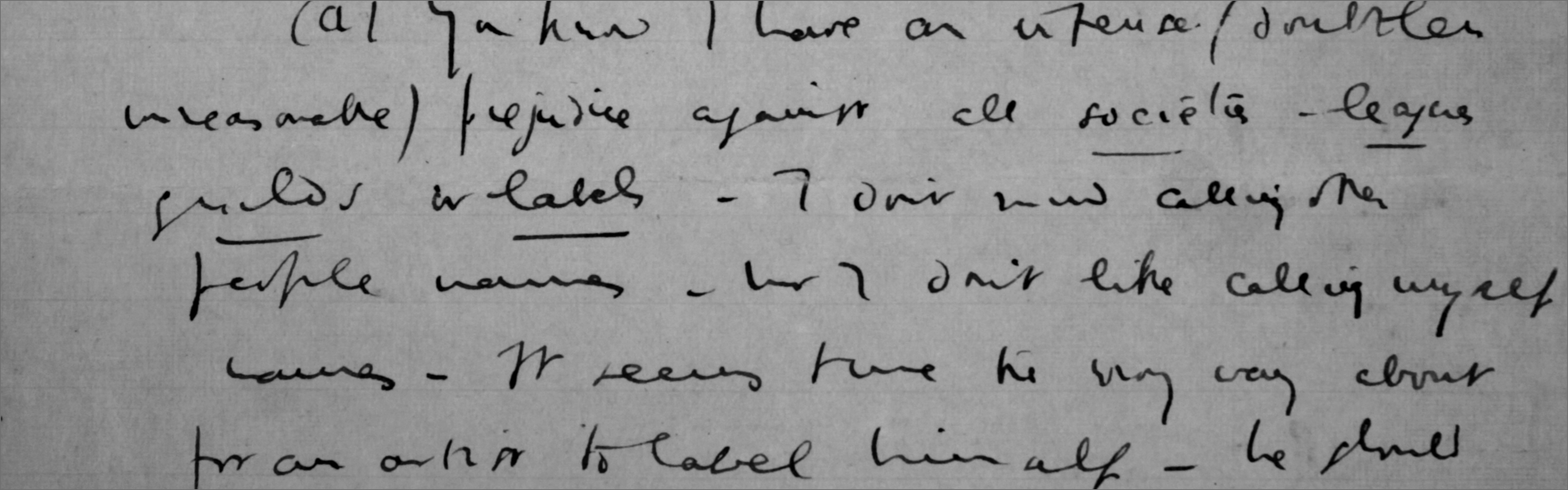

Letter from Ralph Vaughan Williams to Harold Child

Letter No. VWL365

Letter from Ralph Vaughan Williams to Harold Child

Letter No.: VWL365

Hotel Latemar

Karersee

Botzen

Tirol

Austria

[About 15th July 1910]

Dear Mr. Child.1

(I hope I spell your name right – I’ve never seen it written!)

First I want to thank you very much for being so kind and sympathetic and apparently actually anxious to cooperate in this operatic venture.

Secondly to remind you that if our scheme ever comes to anything then it will never get past pen on paper – for I see hardly any chance of an opera by an English composer ever being produced, at all events in our lifetime – does this make any difference to your entering into the scheme?

Thirdly, this is the letter which I promised with my ideas on the particular kind of opera I had an idea we might cooperate on – please forgive the extreme length. I have a lot of nebulous ideas as to how an opera should be made which I have tried to work out on a small scale by myself – but have come to the conclusion that what I must try and do first is to get some practical knowledge of the stage* and for this purpose I want to try my hand at an opera on more or less accepted lines – preferably a comedy – to be full of tunes, and lively, and one tune that will really come off:

*I have already found this to a very small extent in some incidental music to plays.

(I’m sorry for talking about myself such a lot but it is inevitable!)

This fitted in with another idea of mine which was to write a musical, what the Germans call ‘Bauern-Comedie’ – only applied to English country life (real as far as possible – not sham) – something on the lines of Smetana’s ‘Verkaufte Braut’.2 For I have an idea that an opera written to real English words – with a certain amount of real English music and also a real English subject might just hit the right nail on the head.

As regards the form – not Wagnerian and not altogether Mozartian – but more the Mozartian with some of his squareness taken away – perhaps a certain amount of the Charpentier – Puccini conversational methods thrown in – but this is all vague and I shd like to fit in with your ideas.

Only I think the whole thing might be folk-songy in character – with a certain amount of real ballad stuff thrown in.

I will now put down some ideas as to scenes I have – which may possibly be useful in case they happen to fit in with any ideas of yours – otherwise please discard them absolutely.

(1) Opening scene, a fair with all the paraphernalia – merry-go-round, cake-stalls, shooting-gallery, fat-woman ‘Show to life guardsman’- a ballad-monger, small boys with whistles, etc. etc. An opening chorus and scene – (not a set chorus ‘the chorus sing the praise of a good glass of beer’) but ejaculations in fragments on a sort of symphonic basis, with lavender cries, people shouting out what they have to sell, etc. and the ballad seller singing bits of ballads – all leading up to a climax when a prize fight is announced – the village champion enters his name (scene between him and his young lady?). No challenger appears till at last a stranger rides (or walks up) (possibly a gypsy – see one of the opening chapters of Borrow’s I Zincali*3)

Defeat of the village champion – heroine feels inclined to transfer her affections to the stranger – disgust of the village hero.

*I am not sure however whether it is in the nature of things for a gypsy to run off with a non-gypsy – which I suppose wd be the inevitable conclusion perhaps the stranger might be some purely fanciful character?

(2) Then would possibly follow a plot to down the stranger by the village hero and his boon companions – possibly a scene late at night in the village inn (or just outside it). The village hero and his friends go out at night intending to come back early in the morning to have their revenge – which is somehow triumphantly frustrated by the stranger who when morning comes rides (or perhaps drives in his little cart) off with the heroine before the whole village and the discomfited village hero.

But before this climax is reached I have an idea for another scene (which will I think fit in with the above) viz.

(3) Early in the morning (still dark) the stranger comes in singing a ballad (see ‘Sweet Europe’ in Sharp’s ‘Folk Songs from Somerset’) which brings the heroine to the window – there follows a scene in which they arrange to go off together (or whatever they do arrange). This starts quietly and conversationally and gradually works up to a duet ‘appassionato’ in which the ballad tune (and possibly part of the words) has a large share – the stranger then goes off, the heroine shuts her window and the dawn gradually comes (empty stage). As soon as it is a little light the Mayers are heard in the far distance-coming back with their branches of May and singing – they gradually get nearer and nearer and fill the stage and the full light gradually comes.

But after all it is you who are to write the play, not me – these ideas are only to be taken for what they are worth.

Or perhaps you want to write something quite different either

(a) all music,

(b) with dialogue,

(c) with melodrama,

perhaps a gay sort of comedy, like Cosí fan Tutte – with purely formal square-cut numbers,

or a purely fantastic opera or an English subject subject of quite a different nature (e.g. The Mayor of Casterbridge).

By the way, I have no objection to the structure being more or less formal & conventional – as I like duets, trios, quartets or even quintets – I think all opera has to be conventional (or perhaps I should say not realistic).

As regards the relationship of words and music – there are I think three grades

(1) Dry recitative, in which the pure facts are set forth

(2) ‘arioso’ or ‘scena’ in which the emotional growth of the drama can be set out

(3) Lyrical sections – which, dramatically, should be pure points of repose (corresponding to such passages as Hamlet’s soliloquies or ‘0 Romeo, wherefore art thou Romeo.’)

The story should not be told in lyrical moments – and one must always remember that it is always difficult to take the logical meaning of a sentence in when it is sung.

Out of the way words and elaborate phraseology does not do in a lyric – because they are in themselves an attempt to supply the decorative element which the music is there to supply.

I think that is all – slow – long tableaux – or long dramatic pauses are always good, as the music takes a long time to speak, much longer than words by themselves – in fact, one wants purely musical effects in an opera just as one wants purely poetical effects in a drama.

I have put down all that occurs to me – but please don’t consider any of it as of any importance.

I am here for about a month,

Yrs very tr[uly]

R. Vaughan Williams.

1. Harold Child was a writer and theatre critic. He regularly contributed leading articles to The Times. Hugh the Drover, Catalogue of Works 1924/1, was his only opera libretto.

2. Smetana’s opera The Bartered Bride has some similarities to Hugh the Drover, in its village setting and core theme of the conflict between a marriage arranged for the heroine by her family and one dictated by the heroine’s own inclinations.

3. A reference to the section ‘The English Gypsies’ in George Borrow’s Introduction to his The Zincali, or An Account of The Gypsies in Spain of 1841 (source of the challenge that recurs in Act I of Hugh the Drover: ‘The best man in England for twenty pounds!’).

4. The outline plot which VW proposes to Child is, broadly speaking, that to which the opera was eventually written. For an outline of the plot in its later form which VW sent to Percy Scholes see VWL501, and for some changes made as the first production at the Royal College of Music was being prepared see VWL566.

-

To:

-

From:

-

Scribe:

-

Names:

-

Subject:

-

Musical Works:

-

Format:

-

General Notes:

This letter is the first of a series written to Harold Child about the opera which is printed substantially complete as Appendix I in R.V.W.: a biography, pp. 402-421. These letters are unusual in the corpus of VW’s letters in that they, and in particular the present letter, give more evidence about the artistic genesis of a work than in any other case. According to the diary of Adeline VW’s mother, they left on holiday on 10th July and returned on 8th August, so the date of the letter would be about 15th July after arrival in the Dolomites. That the year was 1910 is confirmed by VW’s remarks on the origins of the opera to Percy Scholes in VWL501.

-

Location Of Copy:

-

Shelfmark Copy:MS Mus. 1714/2/4, ff.1-9

-

Citation:Cobbe 63