Letter from Ralph Vaughan Williams to Hubert Clifford

Letter No. VWL662

Letter from Ralph Vaughan Williams to Hubert Clifford

Letter No.: VWL662

From R. Vaughan Williams,

The White Gates,

Westcott Road,

Dorking.

[Early 1939]

Dear Clifford1

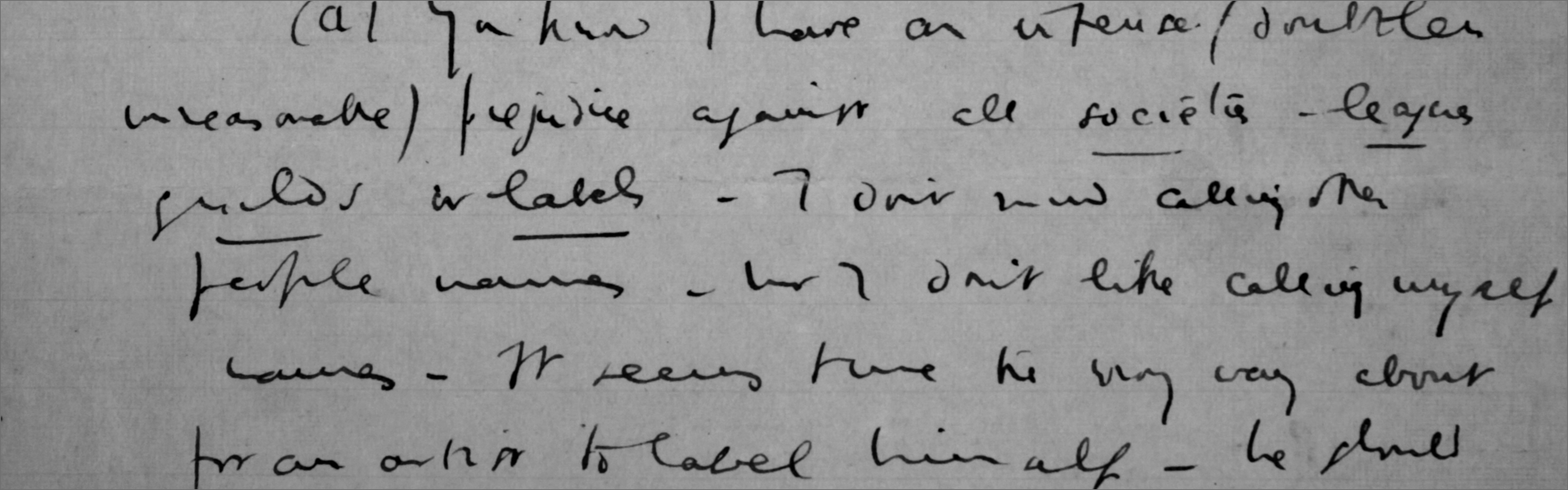

Will the enclosed screed be any use to you – If so I suggest you should have it typed & I will correct the type script before it goes to the printer

I have been much interested in the book & think it excellent – I have spotted one or two apparent misprints.

& one point I should like you to elaborate about – the inexperienced conductor. It is my own experience but I have never seen it mentioned in any of the text books. When I first waved a stick I felt like playing the piano or organ & went on moving my stick till I heard the sound – Now of course the sound comes to the conductor’s ear a fraction late & the music got slower & slower.

– I think it is important to point out to the conductor that he must go on to the next beat as soon as ever he reaches the point where he thinks the sound ought to come whether to his ears the sound has come or not

Yrs

R. Vaughan Williams

PREFACE

In this book Mr. Clifford preaches the gospel, to which I cordially subscribe, that if the art of a country is to be vital, we must be doers of the word and not hearers only.

We owe much to the Radio and the Record, but these wonderful inventions have their comcomitant dangers. I once examined a candidate for a musical scholarship. I asked him: `What is your favourite piece of music?’ – he answered, `The Prelude to Tristan,’ but he was unable to play or even hum the opening phrase. His knowledge was entirely obtained from sitting in his armchair and smoking his pipe while he turned on the gramophone. Now in my young days our only method of studying great music was to strum out the score for ourselves, preferably by means of the now neglected art the pianoforte duet, or to join an amateur orchestra. Those who have studied the great masters from the humble position of last desk in the 2nd violins of an amateur orchestra get to know them in a way which the gramophonist can never achieve.

If all the world is content to listen there will soon be nobody left to listen to. At present we still have with us great artists both to delight our ears and to set a standard for the humble amateurs respectfully to imitate; but expert performers are not like old soldiers; they will, alas one day die and their places will have to be filled up. Whence can the recruits be enlisted better than from the school orchestra? This is not to say that every school boy is a budding Kreisler, but that where the embryo genius exists the school orchestra will find him out, such cases are by no means uncommon in the experience of school music teachers.

There is a well known “Punch” picture of a cynical old gentleman listening to an amateur quartet. “Do you get any pleasure out of your playing?” he asks, “Oh, yes” is the enthusiastic reply. “That, I suppose , is some compensation for the pain you must cause others.” The conductor of a school orchestra must not expect in his early stages that the mere listener will get pure aesthetic pleasure out of the result, nor, indeed should this be his object. It is the players themselves who count; if they obtain spiritual exaltation from their communion with the classics, however imperfect, provided the desire for perfection is there, then the battle is won and the listener, if he has ears to hear, will find something which the most expert performance, listened to in the purely critical spirit, will not give him.

Mr. Clifford’s book is at once idealistic and practical. he aims at the highest but he does not shirk the various makeshifts which are inevitable in amateur music. The aesthete may be appalled, but I believe that Beethoven or Schubert, and certainly Bach, would not have made any objection to the transference of their horn parts to saxophones, to the eking out of the violas by violins, to the occasional simplification of an awkward passage, to a discreet euphonium helping the double basses, to the presence of the harmless pianoforte to strengthen the inner parts, as long as the true spirit of the composition remained unimpaired. All art is a compromise and some of the greatest strokes of genius have arisen from the necessities of an imperfect instrument.

A great man does not appear suddenly out of the sky, he is the product of his surroundings. If we want perfect music in England it will only come as the final result of a great mass of imperfect music. The great composer nearly always springs from artistically humble circumstances. Verdi first learnt his art by hearing his first efforts played on the band of his native town. Dvorak’s early compositions were written for the village band organized by his father the local butcher. In England today after a dark period we are gradually winning the battle of music, our Waterloo will be won in the music rooms of our schools.

R. Vaughan Williams

1. Australian composer and teacher, who settled in the UK. He taught at the County School for Boys at Beckenham 1930-1940 and was author of The School Orchestra: a Comprehensive Manual for Conductors (Winthrop Rogers edition, London 19390, to which he had asked VW to provide this preface. The publication was deposited in the British Museum and stamped on 7th June 1939.

-

To:

-

From:

-

Scribe:

-

Subject:

-

Format:

-

Location Of Original:

-

Location Of Copy:

-

Citation:Cobbe 313