Letter from Ralph Vaughan Williams to Lord Kennet

Letter No. VWL1537

Letter from Ralph Vaughan Williams to Lord Kennet

Letter No.: VWL1537

From R. Vaughan Williams,

The White Gates,

Westcott Road,

Dorking.

May 20th, 1941.

Dear Kennet,1

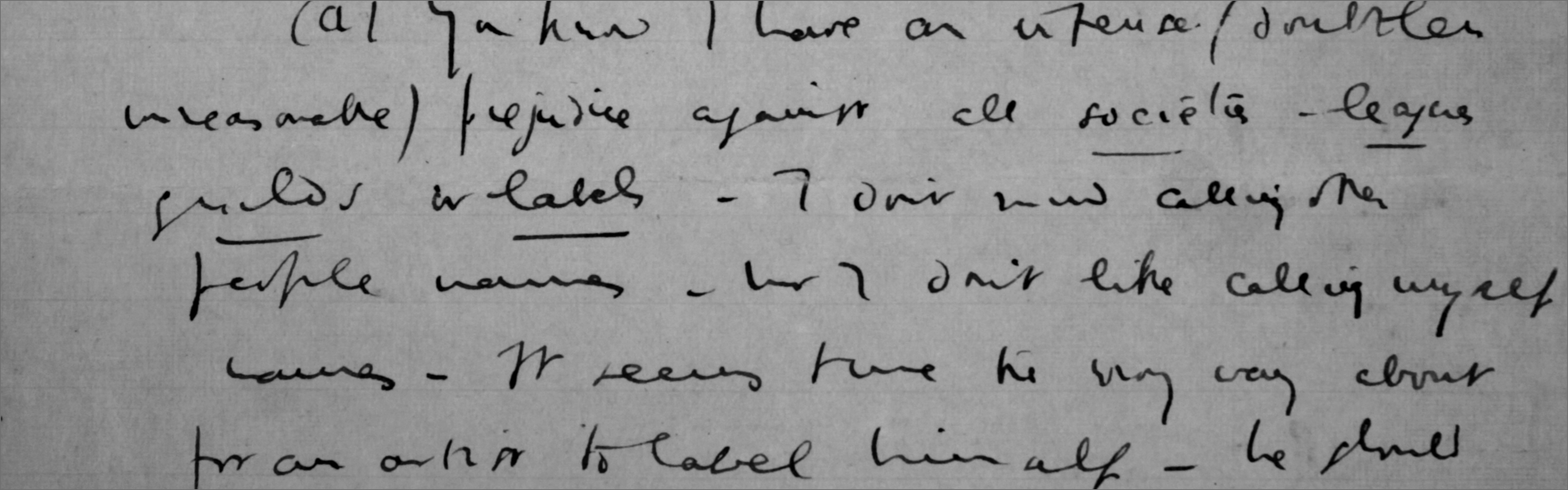

I apologise for the delay in answering – you sent your letter to my cousin Roland2 – it was forwarded twice to him and then on to me. Also I wanted to think the whole thing over, which took some time. I fear my letter has developed into an essay – so I enclose [it] on separate sheets.

I am delighted if I can do anything to help your son – both for our old friendship and for his sake.

Yours sincerely

R. Vaughan Williams

_______________________________

I understand that when your son says he wants to go in for music he means first and foremost he wants to be a composer.

I presume he will have to earn his living; even if it is not absolutely necessary he will probably think it desirable.

Now composing “serious” music is very seldom a paying proposition, at all events in the early stages of one’s career.

Very few of the Great Masters earned their living by their compositions – Bach was a schoolmaster and organist – Beethoven lived partly by giving pianoforte lessons and partly by a pension – Schubert and Mozart lived in miserable poverty and died early – Wagner was a conductor at the Dresden Opera till he was about 30 and sponged on his friends for the rest of his life – Brahms was approaching middle age before he was able to give up concert playing etc.

It may sound very egotistical, but I think it may help you if I tell you a little about myself. I am now making a good income by my compositions, though they are not of the “popular” order. But I did not achieve this until I was about 40 and it is quite precarious and may stop any minute. So except for the fact that I was born with a very small silver spoon in my mouth I could not financially afford to devote my whole time to composition – from the age from about 20 to 30 I supplemented my income by playing the organ (very badly) and teaching and lecturing.

The upshot seems to be that a composer of serious music must at the beginning of his career, at all events, have some other means of livelihood – either musical, in the technical, but alas, not often in the true sense of the word, or something outside music (1) He can be an executant but to be a performer nowadays demands a very high standard: an ordinary student at the Royal College can do technical feats which 50 years ago would have been considered the province of a virtuoso. It is rather late at the age of 17 to start acquiring the necessary co-ordination of muscle and brain to achieve this. So I think the chances are against his being able to achieve sufficient professional skill as a performer. There are, of course, exceptions – Pugno,3 I believe, started his professional career at 40 but he was already a skilled amateur pianist. A wind instrument, I think, is more possible but I do not know that to be an orchestral trombonist is an attractive career. (2) A School job – This requires more general musical knowledge and less special virtuosity, but the music master at a Public School is usually expected to be a competent organist. In a job like this I think that a general educational background like the history tripos would be a help. (3) He might become one of the young men at the B.B.C., but again unless he has special qualifications as conductor or performer it is rather a dim job. One young friend of mine started as a conductor at a provincial B.B.C. He was very musical but I think not sufficiently technically skilled and now, as far as I can make out he is acting as a sort of superior messenger boy at the B.B.C.

The snag about all musical jobs is that they involve a lot of unmusical work. On the one hand you do not get right away from music in your working hours as you would do if you were a solicitor or a scientist. You have to spend a lot of time playing and conducting music you hate, teaching unwilling and unmusical pupils etc. This leaves you just as little leisure for real music as being in an office but, unlike being in an office, you have “music” of a sort in your mind and in your ears all day long: therefore you do not come fresh when the work is over to the music which is in your soul. People of very strong character can fight against this – Gustav Holst for some years earned his living as a trombone player in a dance band dressed up as a “blue Hungarian”, but it was a desperate struggle.

There is much then to be said for earning your living outside music and being a “spare time” composer. On the other hand it is essential for a composer to be in touch with practical music – playing in an orchestra – singing in a chorus – conducting and teaching – doing all the odd jobs of arranging, orchestrating etc. by which composers eke out their livelihood, all this helps the composer keep the necessary proportion between the world of facts and the world of dreams – Wagner I am sure would not have achieved his mastery over the orchestra if he had not been for some years conductor of the Dresden Opera, Brahms would have obtained a surer touch if he had not refused the post of conductor at Düsseldorf (?) – Delius would perhaps have had more backbone in his music if he had gone down into the arena and fought with beasts at Ephesus instead of living the life beautiful in a villa in France.4

On the whole – but with many doubts I vote for history – your son says that music will take up his whole time. By this I guess he means composing music.

Now my advice to young composers is “don’t”. I know by personal experience that the young composer thinks that what he is writing is what the world is waiting for – and I should not think much of him unless he did think so – but he also thinks that it must be done here and now and that tomorrow will be too late – not realizing that if he studies and learns now the masterpiece will come later – and that at the age of 17 he has got all his life before him.

I think it was Smetana who as a young man realized this and set to work on his intensive study of the Great Masters. This study, it seems to me, can to a certain extent, be combined with History lectures. Let him not despise the humble counterpoint exercise – not necessarily with a master. Let him one day look at a bit of Palestrina and try and write something if only a dozen bars that sound more or less like it. Let him look at the Bach Inventions and then experiment in what we call “bad Bach”. He should always have a miniature score in his pocket and look at it in trains and buses and hear as much music as possible. All this – it seems to me – can be spare time work.

Your son raises the question of where to study after the war and queries Leipsig. I do not know the answer with regard to executive music though I believe that except for virtuoso training here is as good as anywhere and Heaven forfend that any one should go to Germany and learn to make a noise like German Oboists, Clarionetists and Horn players. However I do feel pretty certain that creative work must grow out of its native soil. My opinion is that the elements of composition can be taught better in this country, partly because less pedantically than abroad. I think it most important that the young composer should mature himself and find his direction in his own surroundings – then when he knows his own mind is the time to go to foreign countries and compare fresh views, to broaden his outlook and fructify his inspiration. Perhaps taking a sort of finishing course with some good foreign teacher, always remembering the attitude of Foreign to English musicians is unsympathetic self-opinionated and pedantic. They believe that their tradition is the only one (this is especially true of the Viennese) and that anything that is not in accordance with that tradition is “wrong” and arises from insular ignorance.

Almost all the British composers who have achieved anything have studied at home and only gone abroad when they were mature – Elgar, Holst, Parry, Bax, Walton. Stanford is an exception, but he was by no means a beginner when he went to study abroad and as a matter of fact never quite recovered from Leipsig. On the other hand I have known many young musicians with a genuine native invention who have gone to Germany or France in their most impressionable years and have come back speaking a musical language which can only be described as broken French or German. They have had their native qualities swamped and never recovered their personality.

This is especially true now when there is so much talk about “new paths” in music. All these young composers do is pick up a few shibboleths of the new language without understanding it, whereas if they were first thoroughly grounded in their native culture they would be able to assimilate anything that was worth while in these supposed new ideas into their own organism.

I am much elated to find that so many young people with the public school tradition are finding that music is a possible means of self expression.

But we must remember – and you of course must know this as well or better than I do – that one cannot tell whether a boy of 17 has the creative impulse or not. At this stage they are bitten by music and naturally they burn to “do it too”. They write out pages of Sibelius, Hindemith or Delius and imagine they are composing. This is an inevitable stage in artistic development, even among the great artists – sometimes the personality emerges, sometime it does not – sometimes the flicker of invention disappears when they eat of the fruit of the tree of knowledge – so we must be prepared for disappointments.5

1. Edward Hilton Young, 1st Baron Kennet, was a Privy Councillor, a writer, and a businessman. His son Wayland Hilton Young (1923-2009) did not follow a career in music but, following wartime service in the Royal Naval, pursued a career as a politician.

2. Roland, son of VW’s uncle, Sir Roland Vaughan Williams.

3. Raoul Pugno, the French pianist, had resumed a concert career in 1893 after having been organist and later choirmaster of the Paris church of St Eugene-Ste Cecile for twenty years.

4. 1 Corinthians chapter 15, verse 32: ‘If after the manner of men I have fought with beasts at Ephesus, what advantageth it me, if the dead rise not? Let us eat and drink; for tomorrow we die’.

-

To:

-

From:

-

Scribe:

-

Names:

-

Subject:

-

Format:

-

Location Of Original:

-

Location Of Copy:

-

Shelfmark Copy:MS Mus. 1714/1/13, ff.149-153

-

Citation:Cobbe 361; R.V.W.: a biography of Ralph Vaughan Williams, p.240-243.