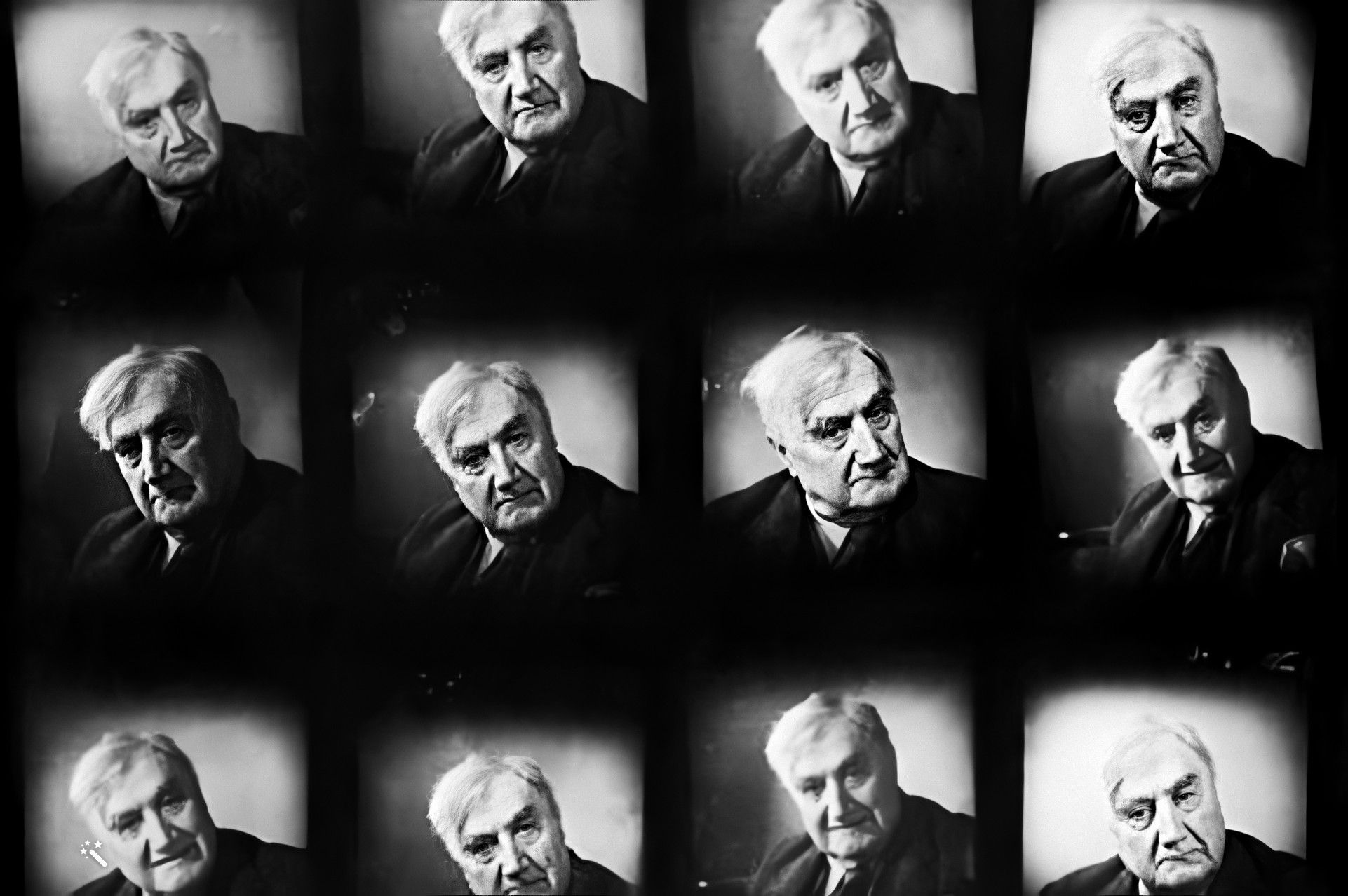

Ceri Owen introduces the composer

When people talk and write about Ralph Vaughan Williams – the 150th anniversary of whose birth is celebrated in 2022-3 – there’s a tendency towards extremes and opposites.

He was an old-fashioned nationalist or a trailblazing modernist. His music was narrowly English or eclectically cosmopolitan, cosy and unchallenging or unnerving and ‘dangerous’ (the last was the view of Peter Maxwell Davies, who paid tribute before he died to Vaughan Williams’s startling modernity – his ‘extraordinary way of going places nobody else was going to’). Over the past few years alone, Vaughan Williams’s best-known work, The Lark Ascending, has been linked to the parochial insularity of Middle England, and also to something quite different. For the writer Richard King, ‘the physical setting of The Lark Ascending is anonymous’: impersonal and ultimately inclusive, this music ‘grants us access to ramble through our mind’s own wild places’.

The variety of these descriptions points to the futility of attempts to pin down or contain Vaughan Williams. He was a unique and complex artist, the many sides of whose work and personality resist categorization. He composed music of remarkable range, beauty, imagination, skill, and depth of feeling. During his lifetime he became renowned as a composer for the concert hall, opera house, church, theatre, school, film, TV, and radio, but also as a folk song collector, hymn editor, conductor, lecturer, writer, broadcaster, and musical and social activist. With iconic works like the Fantasia on a Theme by Thomas Tallis (1910), he reached deep into England’s musical past to create a radical new sound world, of a kind never heard before. In the years thereafter he became a household name in England, and by the Second World War was widely considered ‘the pride of the nation’, as the writer Elias Canetti observed.

Yet, after Vaughan Williams’s death in 1958, much of his music was neglected. Perhaps this was due to his association with the narrow version of English identity referenced above. Some listeners still cling to this portrait, while others notice the ambivalence of supposedly reactionary, escapist idylls evoked in works like the Pastoral Symphony (1922). The marks left on his music by the First World War, and by Continental modernism, are increasingly explored, and more is understood of his political beliefs, which placed emphasis on cultural nationalism in the context of international co-operation.

A colossal body of work, Vaughan Williams’s symphonies open up vast terrains of emotion and experience, from the elegiac, dramatic but gentle Pastoral Symphony; to the furious, bleak, and vivid Fourth (often considered one of his more obviously modernist works); to the optimistic, spiritual, and serene Fifth, to name just three. Yet, different as each of his symphonies are, they’re also unmistakably his. Vaughan Williams’s output is so rich in self-quotation and allusion, for me, his work offers versions as much of what English music might be, as versions of who Vaughan Williams might be.

But the idea that he was driven above all by a need to express himself is complex, because he also felt a duty to equip others with this gift. For that reason he composed music that anyone could sing, from the child in school to the community choral member to the hymn-singer in church. He conducted amateur choirs and orchestras throughout his career, even when a composer of international repute, because he believed the role of the amateur within musical culture to be as vital as that of the professional.

One of his most far-reaching projects was the provision of music for The English Hymnal. Concurrent with activity as a folk collector and editor of early English music, his work on the Hymnal allowed him to preserve and reinvigorate sounds that were falling silent, or had already been forgotten. By fashioning them into hymns, he ‘returned to the mouths of the people’ melodies that would otherwise be lost. Though paternalistic in appointing himself a guardian of musical culture, his aim was to provide ‘good music’ to which everyone had access, if nowhere else than in Church. He believed that music afforded an experience of spiritual transcendence, and that this should be open to all.

Perhaps that’s why he also made time to campaign for countless musical and social causes. Many of the institutions to which he lent his support still provide a lifeline for the arts (Arts Council England and Help Musicians are two of very many). The help he offered to younger or struggling composers has always been well known, and the Trust he established to preserve this legacy (RVW Trust – now Vaughan Williams Foundation) continues to promote new music to this day.

But Vaughan Williams’s influence reaches far beyond the world of ‘classical’ music (a term he seemed to dislike), and it always has. We’re reminded of this by the artists who have admired or owned a debt to his work: not just composers like Harrison Birtwistle and Mark-Anthony Turnage, but musicians working across folk, rock, electronic, jazz, and experimental genres – Richard Thompson and Neil Tennant; Chris Wood and Kit Downes; Barbara Dickson and Mara Carlyle.

Ralph Vaughan Williams made a vital and inestimable contribution to twentieth-century music and musical life, especially but not exclusively in England. His music still speaks to listeners today because it searches, for ways of feeling and ways of being. It articulates different – and often ambivalent – identities, different points of view, which jostle side by side, check by jowl. The anniversary celebrations offer opportunities to hear the full range of Vaughan Williams’s output, and to listen beyond the opposing voices that will likely seek to claim it, turning attention instead to his music’s endless complexity, nuance, and sense of paradox.

Ceri Owen, November 2020

Ceri Owen is a Welsh academic, pianist, and writer. She is working on a new biography of Vaughan Williams.