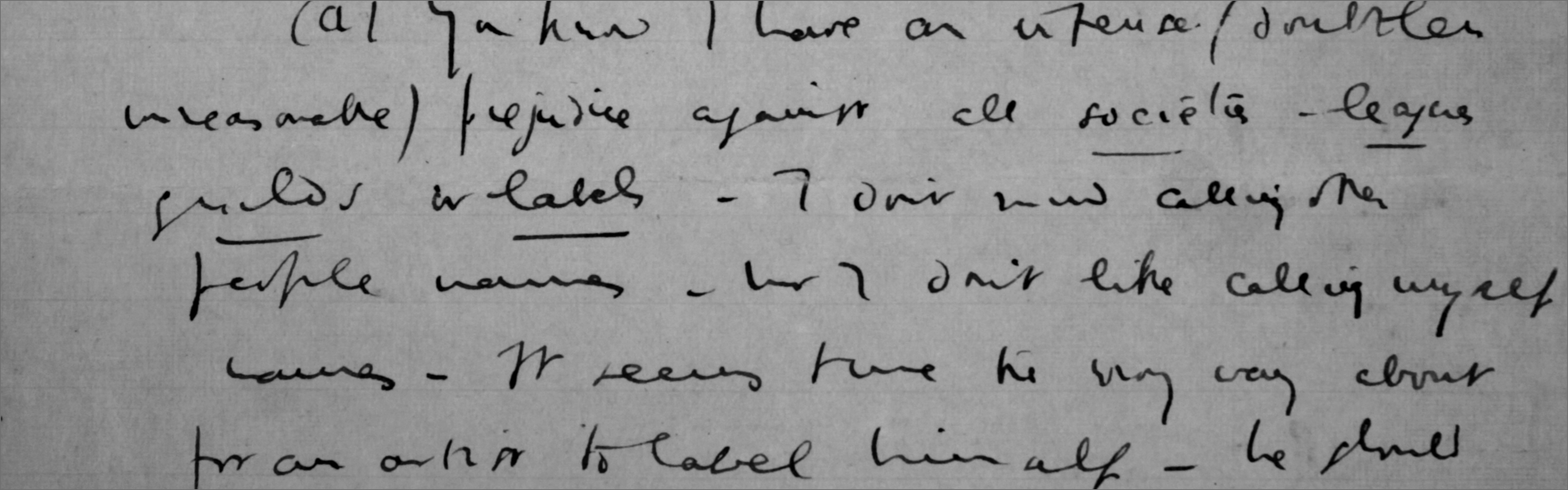

Letter from Charles Parker to Ralph Vaughan Williams

Letter No. VWL3339

Letter from Charles Parker to Ralph Vaughan Williams

Letter No.: VWL3339

21st February 1958

Dear Dr. Vaughan Williams,

I am very much in need of your help and advice. You will, I hope, remember me as the producer of the Elgar Centenary programme last year – we met with Alec Robertson when you recorded your own reminiscences for the programme.1

I am going to find it very difficult to explain the occasion for this letter, and really what I would like to do would be to call upon you and ask you to listen to some of my work as a producer, in particular two programmes, one called “Sing Christmas and Turn of the Year” which I produced on Christmas Morning, and another called “The Ballad of John Axon”, which has not yet been broadcast. Each of them runs an hour I am afraid, but it is because of these programmes – and what I believe they stand for – that, at the moment, I find myself in revolt against the orthodoxy and mumbo-jumbo of the BBC, and I desperately need the opinion of and, I hope, support, of such a one as yourself to give me my bearings and strengthen my arm.

You see, I am not a trained musician. I have for fifteen years been increasingly concerned with folk music, English and American, and have become more and more convinced of the profound beauty of English folk song and increasingly frustrated and bewildered on the one hand by the seeming inability of ordinary people to perceive the wonders of their own tradition, and on the other, the purist and archival attitudes of so many of the champions of folk song as such. My work as a Features producer takes me, with a midget tape recorder, among the industrial population, and my frustration is intensified when I come across, as I continually do, this same strand of poetry and deep sense of feeling that is English expressed in idioms and styles that are so desperately unworthy of the people themselves. What I believe may be happening is, that this present younger generation is rejecting the secondhand American popular musical idioms and is feeling increasingly towards a real and quite uninhibited acceptance of traditional music.

I have, these past six weeks, been present at the Princess Louise Restaurant in High Holborn where, at 7 p.m. every Sunday evening, two or three hundred people cram themselves into a room to hear the most extraordinary collection of folk songs from the most austere and stark unaccompanied ballad to the most rhythmic American blues, where one witnesses eighteen or nineteen year olds discovering modal forms, and hears “Blood Red Roses”, “The Bonny Ship the Diamond”. “The Derby Ram” and a hundred other grand songs sung with a joy and freshness of feeling that I find most moving. In fact, I have jumped the gun on the BBC by recording the last five sessions in the hope that perhaps, in time, one enlightened planner might realise that here could be the dawn of a new and truly popular idiom. In “Sing Christmas and the Turn of the Year” I tried to give expression to a catholicity and a feeling for music of this sort to match the occasion, and bring together the orthodox church choir, and folk singer, and skiffle group, the country fiddler and the Gaelic and the hundred and one other elements that make up this still overwhelming, rich musical inheritage2 of Britain.

In “The Ballad of John Axon” I have tried to produce, true to tradition, a contemporary epic – the story of a goods train driver who last year was awarded the George Cross posthumously for staying on the footplate of a runaway locomotive on a seven mile gradient in the Peak district. Here, I have tried also to extend the boundaries of sound radio itself by making new and dramatic use of actuality and placing real people in a musical context.

Forgive me, sir, if I trespass upon your time by writing like this. I cannot but believe that the truths to which I am, in my muddled way, feeling, are something of the same truths which you have for so long given superb expression. The brashness, the musical idioms, the bringing together of the organum and the hottest of jazz – these may offend, but it is, I believe, so very important that the whole body of music be brought back together; that lines of communication be opened across the whole musical spectrum, and that the wisdom of such a one as yourself be available to sincere upstarts like me.

I hope I have been able to convince you of my serious purpose in asking to call upon you. A recording engineer in Birmingham – one Mary Baker – once told me that when you were presiding at an E.F.D.S.S. Meeting, you shocked her by saying that only when the society could itself go into liquidation could it reckon to be successful. I am convinced that the time is ripe for English folk song to come into its own. Great dangers will attend the inevitable changes which it must undergo to become truly popular.

Please may I talk to you? I can come to London at any time to suit your convenience.

Yours sincerely,

Charles Parker

Senior Features Producer

Midland Region

1. See VWL3488.

2. i.e inheritance

3. English Folk Dance and Song Society

-

To:

-

From:

-

Names:

-

Subject:

-

Format:

-

General Notes:

Letter sent via Duncan Hinnells. Typewritten.

-

Location Of Original: