Transcript of VW’s contribution to Elgar Centenary Programme on the BBC

Letter No. VWL3488

Transcript of VW’s contribution to Elgar Centenary Programme on the BBC

Letter No.: VWL3488

[May 1957]

Transcript of VW’s contribution to Elgar Centenary Programme on the BBC1

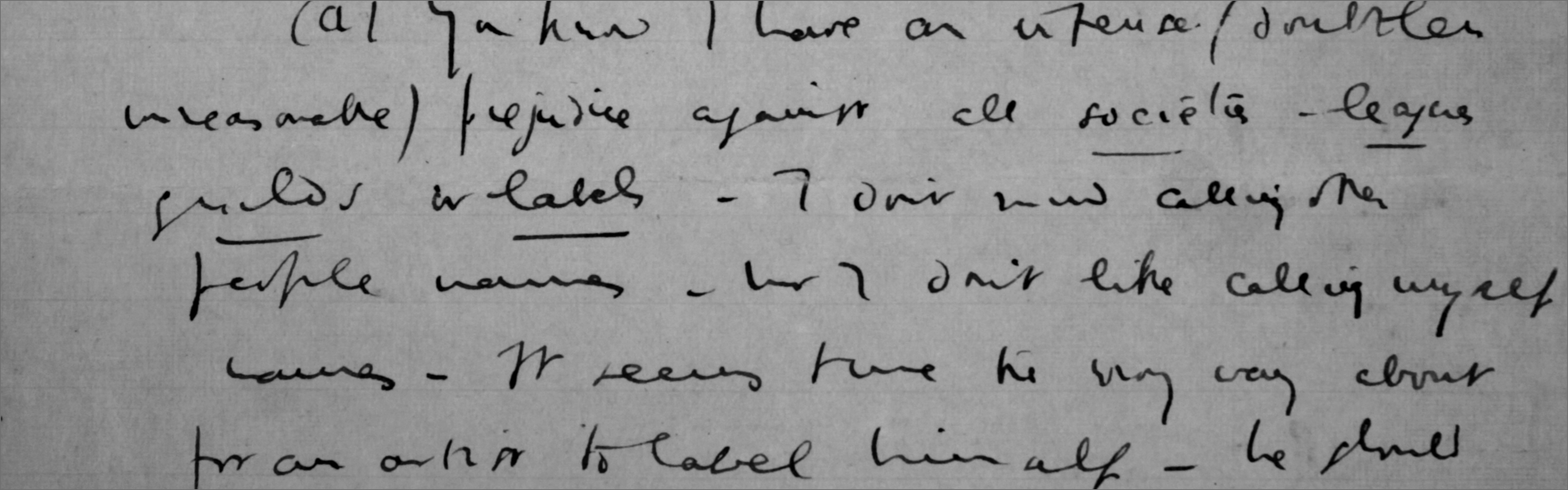

My first knowledge of Elgar’s music was a performance – shortly before 1900, of the Variations. Here was something new, yet old: strange, yet familiar: universal, yet typically English. (By the way, most critics imagine Elgar is being most English when he is being rumbustious and Pomp-&-Circumstancy: my opinion is that Elgar is most English when he is romantically nostalgic, as in the slow movement of his string Serenade.)

My next experience of Elgar was the first performance of “Gerontius”. I have to confess that on first hearing I was very disappointed – I know better now.2

The first time I addressed Elgar personally was by a “Dear Sir” letter, early in the 1900s, when I wrote and asked him to give me lessons in composition, and received a polite answer from Lady Elgar saying that her husband was too busy at the moment, and advising me to apply to Bantock!

The first time, I think, when I had a conversation with Elgar was on the occasion of a performance of his violoncello Concerto, when he approached me rather truculently and said – “I am surprised, Dr Vaughan Williams, that you care to listen to this vulgar stuff!” The truth was, I think, that he was feeling sore over an accusation of vulgarity made against him by a well known musicologist, who Elgar probably knew was a friend of mine.3 I did not meet him again for some years, and then he was always gracious and friendly. He wished us to be on christian name terms, and even invited me to call him Teddy. This I could not do. He was at least ten years older than me, and was already famous, so I compromised, agreeing to drop Sir, and Dr.

He came to hear a performance of my Sancta Civitas, and gave it generous praise. He told me that he had some thought of setting the words himself “But I shall never do that now” to which I could only answer that this made me sorry that I had ever attempted to make a setting myself.

Not long before his death I met him at the Three Choirs, and he talked to me about Skelton, of whom I knew little then, except through the Anthologies. He said “You should make an oratorio out of Elinor Rumming”. He went on to point out how the metre of Skelton was often pure jazz. I remembered this when following his advice I attempted a setting.4

I once sat next to Elgar at a rehearsal of Parry’s symphonic variations, and was struck by their curious, spiky sound. I said “I suppose this ought to be considered bad orchestration, but I like it”. Elgar turned on me, almost fiercely, and said “Of course its not bad orchestration, this music could be scored in no other way”.

I should like to finish off with a small technical point: in the introduction to Elgar’s first Symphony the melody is given to fairly heavy woodwind. The bass violoncellos and double basses playing détachées, while the inner harmony is left to two muted horns. This looks all wrong but sounds all right. Here indeed we have a mystery and a miracle.5

1. This transcript was sent to UVW in 1959 by Charles Parker who had produced the programme in 1957. In a covering letter he said ‘…at first he was very reluctant to be recorded, although of course when he finally agreed to do so he was quite superb and I in fact used the recording for the very end of the programme’. See also VWL3487. The transcript from the recording differs and is VWL3505.

2. In the written transcript this paragraph comes at the end but in the transcript from the actual broadcast it is amended and placed about here. See VWL3505.

3. This was Edward Dent, writing in a German paper (ex.inf. Duncan Hinnells – check).

4. i.e. Five Tudor Portraits, Catalogue of Works 1935/5.

5. VW wrote to Michael Kennedy about this – see VWL3509.

-

From:

-

Names:

-

Subject:

-

Musical Works:

-

Format:

-

General Notes:

Typewritten.

-

Location Of Copy: