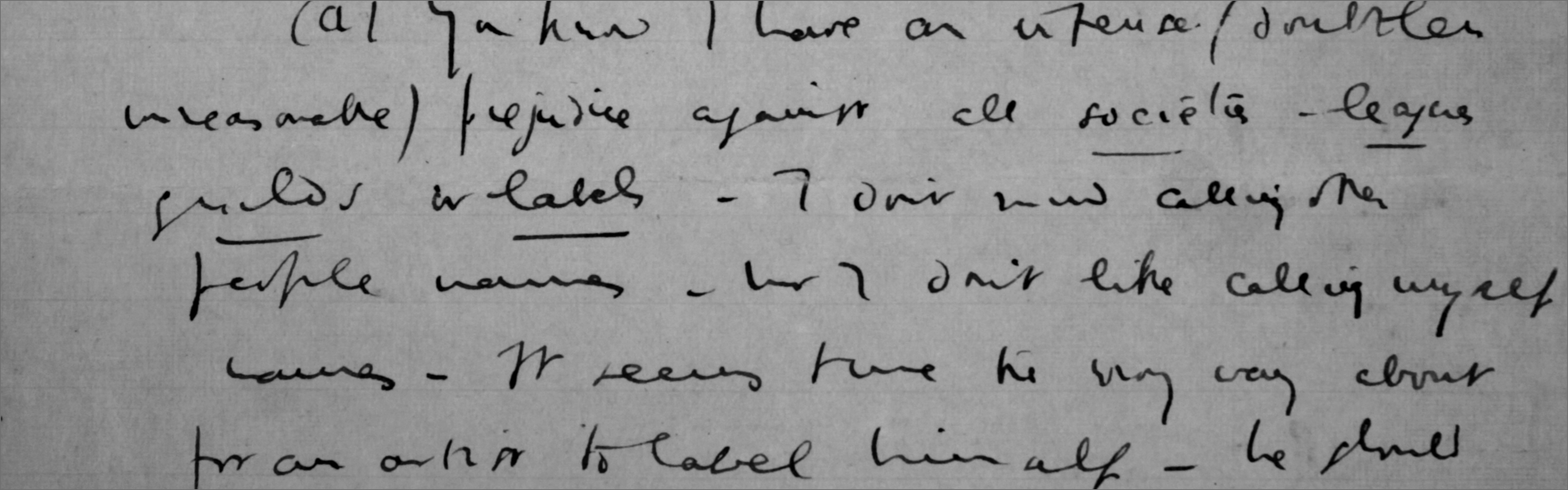

Letter from Ralph Vaughan Williams to Frank Howes

Letter No. VWL512

Letter from Ralph Vaughan Williams to Frank Howes

Letter No.: VWL512

From R. Vaughan Williams,

The White Gates,

Westcott Road,

Dorking.

[1937?]

Dear Howes

As you were good enough to put me in touch with Mr Strasser,1 I think I ought to send you, in confidence, a copy of my letter to him

yrs

RVW

The White Gates,

Dorking.

Dear [Mr Strasser]

I have delayed answering your letter because I wanted to make my position clear to myself, as well as to you.

I fear this is going to be a long letter.

The problem of opera in England is a difficult one and much of its future welfare depends on whether we adopt a long or a short-term policy.

Glyndbourne2, for example, was an instance of short-term policy. It provided a wonderful and beautiful entertainment for those who could afford it. But it has not built for the future. It has done nothing toward fertilizing the dormant seed of English opera (i.e., opera for English people – not necessarily by English composers). It did not attempt to study the English temperament (both as regards performers and listeners) and mould or fructify it in the direction of opera. It took no account either, in acting or singing, of English reaction to art. It simply planted continental opera on a foreign soil. The few English performers who were allowed to perform had to conform to continental standards – with fatal results – they could not sing or act in the continental way and they lost their own method. They merely became, in most cases, bad imitations of continental singers.

We shall always be grateful to Glyndbourne for setting a very high standard of execution according to the standard of those responsible. But opera on the “Glyndbourne” principle will always remain an exotic. It is like a bunch of flowers in a glass of water – very lovely while it lasts but having no roots in the soil.

I fear the trouble is that continental musicians (believing in their hearts that we in England are quite unmusical (though they do not dare to say so) consider that their standard is “right” and that every other standard is “wrong”.

Let me give you two examples:

I was told by a high authority at Glyndbourne that the opera at Sadlers Wells was “very bad”. On enquiry I found that this only meant that in a few particulars it differed from that at Glyndbourne. So this official had been taught that everything different was necessarily bad. Or, to give another example – I asked why a lady who is, to my mind, an ideal Mozart singer had not been engaged and I was told that her style was too “instrumental” – while the lady who did sing and was much admired by continental authorities, seemed to me to make a noise like a puppy being whipped!

What course are we to pursue? Are we to take the English standard of singer and mould it to opera, or are we to force the continental style down English throats and hold that their singers, like champagne and caviare, are things which must be imported from abroad because the English soil will not grow such things?

Therefore it seems to me that these foreign artists whom we welcome here – if they are to become good citizens to our musical policy, must not try to impose their culture en bloc on us (as if we were musically a conquered country) but join in our musical life and fertilise it by their own incomparable experience and tradition – Not try to destroy our small and weak tradition, which can easily be destroyed like a weak flame, if we are not careful.

Perhaps, however, you really think that we in England have no musical tradition worth speaking of and that the continental tradition is the only one worth having. (The doctrine of “Herrenvolk” is not confined to the Nazis).*

Do you, in fact wish to establish a little “Europe in England” quite cut off from the cultural life of this country and living for itself alone? – and affecting among Englishmen only those snobs and prigs who think that foreign culture is the only one worth having – who do not recognise the intimate connection between art and life.

I put this point to the leader of the Free League of German Culture. He replied by offering to do some of my songs at one of their meetings! This was, of course, adding insult to injury.

If musical life in this country is merely to be a bad imitation of continental methods it is doomed. See the awful results at Sadlers Wells of smearing themselves with the droppings of the Russian Ballet.

Now, to come from the general to the particular, all vital opera in England must be sung in English.

If I wanted to prove that the English were unmusical I should point to the fact that we are content to listen to opera in a foreign language.

This attitude is typified by the story of th fashionable lady who, when offered a libretto said “We don’t want to know what the opera is about, we’ve only come to hear the singing”.

Opera in a foreign tongue will only appeal to the snobs who want to hear expensive foreign artists, or the prigs who cannot bear the sound of their own language. It will not touch the people – those who are eventually going to make opera in this country.

This question of opera in English carries a lot in its train. You do not, I presume, propose to do opera in English exactly as you would in German or Italian – the phrasing, the pace, the acting must all be different.

The English attitude towards both tragedy and comedy is so entirely different from the Teutonic or the Latin.

It was painful to me to hear great artists like Roy Henderson and Heddle Nash trying conscientiously to be funny in the Teutonic manner. The hectic boisterousness of the Teutonic manner was absolutely alien to the English nature, whose comedy depends so much on understatement.

Perhaps, however, you propose to give opera, language and all, exactly as they are done on the continent. If native opera were in a very flourishing state in England I would applaud this as a very wholesome correction to our national pride. But in music we have no national pride, we are only too willing to abase ourselves before the foreign conqueror. Our opera, especially, is a tender plant, and only to ready to expire at the slightest adverse blast.

Your task, it seems to me, is to become musically an English man and to see music as we see it and then add to it your own unique experience and knowledge.

Take the existing institutions – Sadlers Wells, Carl Rosa, ‘Intimate Opera’ – join in with them and help them with your knowledge – unobtrusively, keeping yourself in the background. You doubtless know the saying, “There is nothing a man cannot achieve if he is willing to forego the cr[e]dit for it.”

(R. Vaughan Williams)

*[I omitted this remark from the original]

1. Jani Strasser, who became head of the music staff at Glyndebourne in 1937. He was later revered as a teacher and trainer by those who had worked under him there. The letter attached reads as if Strasser, a refugee from Vienna, had sought VW’s advice, at Frank Howes’s suggestion, about taking the job.

2. sic.

-

To:

-

From:

-

Scribe:

-

Names:

-

Subject:

-

Places:

-

Format:

-

General Notes:

Date inferred from content.

The enclosed letter is typewritten. -

Location Of Original:

-

Shelfmark:Deposit 2009/21, Box 1

-

Location Of Copy:

-

Shelfmark Copy:MS Mus. 1714/2/5, ff. 126-129