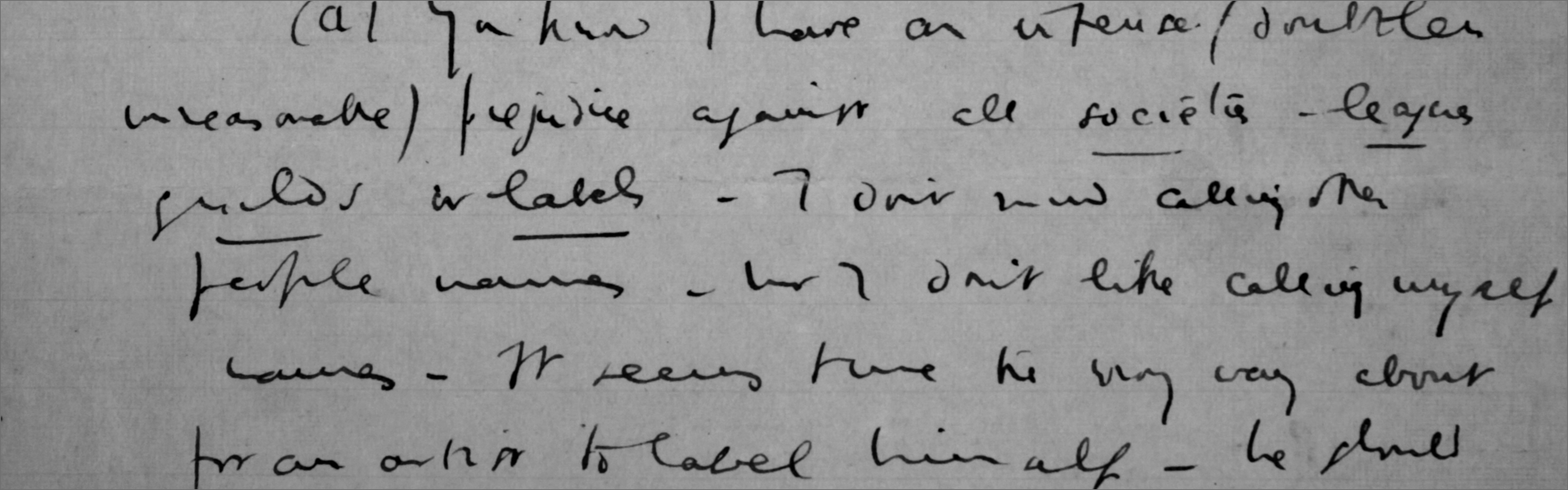

Letter from Olin Downes to Ralph Vaughan Williams

Letter No. VWL3904

Letter from Olin Downes to Ralph Vaughan Williams

Letter No.: VWL3904

August 18, 1953

Dear Mr. Vaughan Williams

I want to tell you of a really wonderful experience that I had recently at what is called the Transylvania Music Camp in Brevard, North Carolina. Brevard is near the Kentucky hill region and is part of the Blue Ridge range where Cecil Sharp made his notable collection of English folk songs on visiting America.

This “Camp” is headed by Mr. James Christian Pfohl, who is an extraordinarily progressive musician and organizer, and has for years been building up music schools in that part of the world, and bids fair, I think, to become one of the most powerful musical forces in the southern part of this country, which has been developing with phenomenal rapidity in music in recent years. For the third time, last week, I made my annual visit to Mr Pfohl and his Camp, where he has instituted what is to me a very interesting procedure, as one of the events of his annual music festival there. This event consists of a discussion by me of some great symphonic work, with the orchestra illustrating my remarks and quoting themes or passages from such work to my own running commentary, for half the program. After this first half of the program there is an intermission, and afterwards the symphony chosen is played without further comment or any interruption to the performance.

The work we chose thus to elucidate was the “London Symphony”. I think you would have been gratified and touched if you had witnessed the response of the audience to its performance. This is a big rustic music shed made of wood, and by no means modern in its architecture or get-up. I don’t know the capacity of the shed, but I would say that some 1,500 or perhaps 1,800 people packed it to capacity, and they listened with an earnestness which you may imagine was most gratifying to me in the discussion of the symphony and the illustrations of passages from the score, and at the end of the concert applauded the work to the echo.

And not a small part of this response comes from something even deeper than the immediate delight of a beautiful work of art. Because I have noticed that the songs sung in that region are not at all of the Broadway or jazz variety, and I think the general character of the thematic material of the “London Symphony” may be nearer to them and more heart-warming than they might be to other less sincere and more spoiled audiences, or, for example, this metropolis1. But it was a wonderful sensation to confront that audience, and to listen with them, and to feel the spontaniety and the vibrancy of their response to the music.

The orchestra consists of about thirty-five percent advanced students of the music camp, reinforced to the extent of about sixty-five percent professional players fom the Cincinnati and other symphony orchestras, who sit by the young musicians in the orchestra, and undoubtedly stabilize them in perfromance, while at the same time the boys and the girls of that Camp, some of whom I understand are not more than thirteen or fourteen years of age, supply a youthfulness and resiliency in performances that are simply wonderful.

Mr. Pfohl led his orchestra with the greatest enthusiasm, and without of course comparing the performance with that of the crack American orchestras, such as those of Philadelphia and Boston, the performance did have a heartiness and a high intelligence, and above all a musical and emotional enthusiasm which was extremely effective. And I may say for myself, that upon returning to the study of the “London Symphony”, I was more deeply impressed than ever by the beauty of the whole conception, and the pregnancy of the themes, and, if I may say so, what to me is their masterly treatment. I daresay that you yourself when you look back upon certain pages of the symphony, feel as I do whenever I look back at particularly bad articles of years ago, to see how much more effectively they could be re-written. You may feel if you took again the score in hand of the “London Symphony” that you would revise certain places, whatever they may be. I myself have been considerably amused, in reading certain English critics and hearing certain English composers talk, and even recalling certain lines that you have written about yourself, in which you are mentioned as an “amateur”. For myself, it has been very advantageous to explore this symphony more closely than I ever have before in preparing my own address, and to realize appallingly how much, how very much, one must know about composition, and what a powerful sincerity and musical motivation there must be to write a symphony as great as that one. I believe this symphony will stand for a very long time, not only for certain distinctions of style and workmanship, but because above all it has in it that breath of the truth, that vision of an artist with that deep feeling which to my mind can only proceed from racial as well as personal sources, which will make us hold this symphony dear for a very long time. I daresay the technician, far more learned than I in the technic of musical composition, including yourself, could point to this or that place, and say, “Why not eliminate that”, or “condense that”, or “extend that”, etc.

But when I think of such issues, I recall the remark of a very dear friend of mine, also a music critic, who has now gone to his rest. My friend said to me: “You know, what the critics said about Wagner, about Chopin, Schumann, Beethoven too, finding weaknesses in their music, were usually true – insofar as they went. The only point is that they didn’t matter”!

There is only one score of yours which goes deeper with me in enjoyment, than the “London Symphony”. That is the “Pastoral Symphony”. I have not yet fully absorbed that latter work, partly because it is too rarely played, and too rarely played, I fancy, because not every one in a predominantly urban civilization has gotten into touch with the true music of nature, which you have. But whatever the merits, or relative merits of these works may be, I say to myself when I hear them, always with renewed delight, “They may or may not be perfect, they may or may not be immortal, but they are music, real music, and they kneel at the shrine of immortal beauty. Whatever else they are or are not – doesn’t matter!”

I learn from Mr. Pfohl that he intends to go to England in some several weeks. He wants very much to see you, and to present you, I think, with a record of his performance of the “London Symphony”. I shall take the liberty of giving him a letter of introduction to you, and know that he would greatly prize the opportunity of calling upon you.

Sincerely yours,

Olin Downes

Mr. Ralph Vaughan Williams

The White Gate,2

Dorking, Surrey,

England.

1. New York.

2. sic.

-

To:

-

From:

-

Names:

-

Subject:

-

Places:

-

Musical Works:

-

Format:

-

General Notes:

Typescript.

-

Location Of Original:

-

Shelfmark:Hargrett Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Olin Downes Papers, MS688, B63, F19

-

Citation:Atlas, Allan W., “Ralph Vaughan Williams and Olin Downes: Newly Uncovered Letters”, Journal of the RVW Society No. 60 (June, 2014)