Address from Ralph Vaughan Williams to the English Folk Dance and Song Society

Letter No. VWL3221

Address from Ralph Vaughan Williams to the English Folk Dance and Song Society

Letter No.: VWL3221

November 12th 1955.

Address to the AGM of the English Folk Dance and Song Society.

We have it on the authority of the Master of the Rolls sitting in judgement, and as good citizens of course we loyally accept it, that Folk Dance is not a fine art.1 But without officially challenging his decision I think we may allow ourselves in private to examine his reasons. He bases his judgement, so far as I can make out, on three points. That folk dance is not creative, that it does not use the mind, that it gives no aesthetic pleasure to the beholder.

The master only knows, as far as I can make out, two folk dances, Sir Roger de Coverley, (country dance), and the Lancers, (square dance) and one singing game, Oranges and Lemons. He has apparently never heard of the Morris or Sword Dance. Nor has he realised that Folk Song as well as dance, plays an important part in our scheme. Folk song, which on no less authority than Hubert Parry, contains specimens of supreme art.

Let us take these three points in turn. First, that folk dance is not creative: but all executive art must be creative, and to dance a folk dance well is as much an act of creation as to play the violin well.

The second point is that it gives no aesthetic pleasure. As I have already said, the Master does not seem to know of the existence of the Morris or the Sword which are definitely by experts designed to give aesthetic pleasure. To my mind the Morris especially can be as truly called high art as the Parthenon or the ninth symphony or Michaelangelo’s Night and Day. The country dance is of course primarily for personal enjoyment. But who can doubt that the figures and steps, when well done, are a source of intense aesthetic pleasure. I need hardly refer again to the artistic quality of many of our beautiful folk songs.

Now is the question of the use of the mind in the folk dance: our Director insists, quite rightly, on the sub-conscious quality of the best folk dancing. But I think he would be the last person to deny that this must be preceeded2 by conscious artistry. To my mind our finest folk dancer was, and indeed still is, the Director himself,3 and I cannot believe that he achieved this supremacy without a gruelling course of technique. I fear that many of our dancers have misunderstood this question, and imagine it does not matter how badly they dance so long as the solar plexus is working alright. I feel sure that the Director would be the last person to insist that mind is not an important part of the folk dancing equipment.

The issue is now officially settled, and has been settled against us; and officially [sic] we bow to the Master’s decision. But might we not persuade him, purely as a private individual to pay us a visit and find out what Folk dancing really is, and whether it is not after all, a fine art.

Of course we must do our part and make sure that our art does not fall from its high position. We must not be content just to jump about and enjoy ourselves. If we set out to enjoy ourselves we shall fail to achieve much enjoyment. If we set out to practise out4 art, and learn how to practice5 as well as we can, then, and then only, we shall achieve the highest enjoyment.

Are we still practising a fine art, as we certainly used to or have we fallen from our high estate[?] I cannot believe it – But it is a serious problem and must be faced

1. The English Folk Dance and Song Society had appealed against a rating assessment, claiming exemption from rates on grounds that it was a society instituted ‘for purposes of … the fine arts exclusively’. In the Court of Appeal the Master of the Rolls, Sir Raymond Evershed, had, in his judgment, pronounced that ‘the activity or “art” (if it is properly so called) of folk dancing and singing is not in any sense creative… In the case of folk dancing and singing the purposes of the Society are not to create anything… but rather to encourage the performance by as many persons as possible of the old and traditional dances and songs in an old and traditional manner. The Society does not claim to appeal to the mind, or even, as I understand it, to the faculty of taste.’ The society had lost the appeal. See English Dance and Song, 20/1 (Sept./Oct. 1955).

2. sic.

3. Douglas Kennedy.

4. sic.

5. sic.

-

To:

-

From:

-

Names:

-

Subject:

-

Format:

-

General Notes:

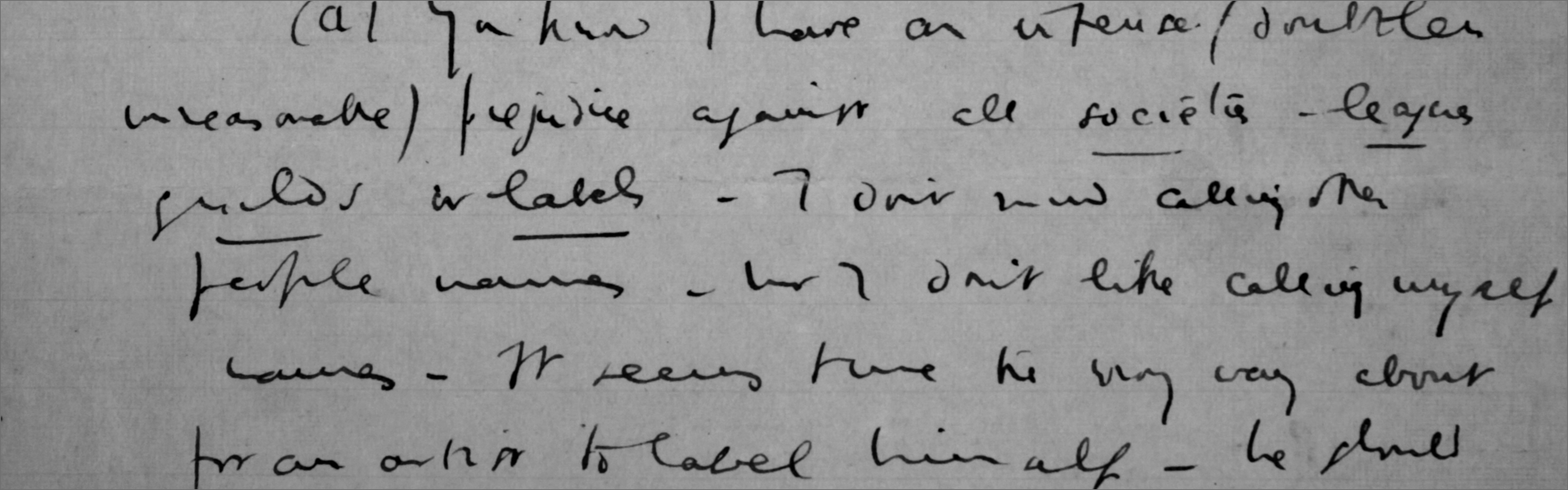

Typewritten with manuscript addition of last line

-

Location Of Original:

-

Shelfmark:MS Mus. 1714/1/21, ff. 123-125

-

Citation:Cobbe 666